Some years ago Roger Fisher[1]penned an interesting paper titled: “Negotiating with the Russians or your spouse: Is there a difference?”. Leaving a little latitude for context, maybe some would prefer to negotiate with Vladmir Putin rather than their spouse, because, they would say, there would be more chance of Mr Putin being flexible than their other half.

Whilst this comparison might draw the odd wry smile, it also raises the issue of what it means to deal with, or be, a tough negotiator. Does it, for example, simply mean inflexibility and adherence to hard lines?

At first instance the answer to the question of what is a tough negotiator raises the issue of context – eg what do we mean when we say parties negotiate? In thinking about ‘negotiating’ the term bargaining might come up and conjure up thoughts of the Monty Python ‘haggle’ skit in the Life of Brian. Our experience and observations (as well as a reflection on Mr Putin and dealing with the other half), however, might then tell us that there is more to it than just a ‘haggle’. But what is the ‘more’?

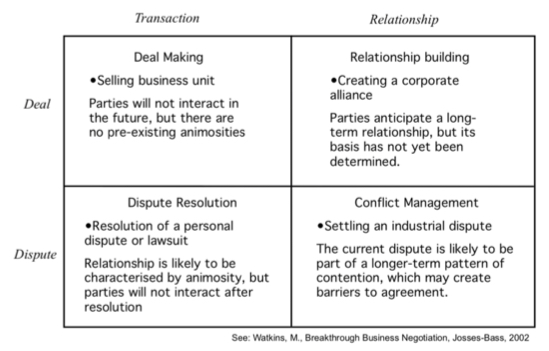

Michael Watkins opens our thinking on negotiation as a process when he describes four different types of negotiation:

Where standeth’ the tough negotiator in each of these types? Think of what of the ‘antics’ might be of a strong advocate lawyer in a lawsuit negotiation. Would those same antics work if taken to the table in trying to collaborate and build a corporate alliance? And what about in the not-for-profit sector, and trying to build a community alliance?

Consideration of the various situations might conjure up thoughts of internal tensions a negotiator might feel at the table. For example, on whether to compete or collaborate; or similarly between motivations to try to claim value or create value; or whether to be empathetic or brutally honest.

As these tensions might mount it is worth remembering that negotiation behaviour is a choice (e.g. at a broad level, we can choose to accommodate, compete, compromise, collaborate, and/or avoid). And all of these choices can have advantages and disadvantages depending on what we are trying to achieve! As negotiators making these choices, we must always be mindful of the ‘Relationship’ between ourselves and those affected by the negotiation – including those on our side of the table.

Thinking about the above issues (in context of us as the tough negotiator), pragmatically what is important in any negotiation is to get the outcome we want. In that sense, it might seem paramount that we ‘convince’, ‘force’, or perhaps even ‘persuade’ the other side to see it from our point of view and to give us what we want. The difficulty with an ‘our perspective’ approach, however, can be that it leaves the other side with a ‘no’ proposition. So here lies the tension: I want to be seen to be the tough negotiator, but if I take the aggressive/assertive approach they may say no. So how do I win?

The interesting point here is ‘win’, and what that means. With this in mind, let’s return to Watkins’ quadrant model above. Each of the situations described by Watkins requires good preparation and an understanding of how the negotiation behaviour choices we make will determine the outcome we get. For example, an open dialogue process suitable for a corporate alliance negotiation may not suit a negotiation for a personal injury lawsuit. Indeed, to take a one-size-fits-all approach can lead you to being exploited. So, is there a method?

If there is one universal, and safe, approach to all situations it is this: Be ‘unconditionally constructive and seek understanding’, but all the while remembering that understanding is not the same as agreeing. If we understand the other side and their needs, interests, concerns, etc , we can work towards the ‘yes-able’ proposition without yielding, or in any way compromising, on our own needs. To achieve that is ‘tough’ work. This was the approach taken by Nelson Mandela in his many years of bringing about change in South Africa, and by any standard he was a tough negotiator.[2]

P Raffles

(Advisor/Negotiator/Coach/Mediator)

[1]The paper ‘Negotiating with the Russians and with your spouse – is there a difference?’, was an unpublished work of Roger Fisher. He is arguably most noted for the text: Fisher, R., Patton, B. and Ury, W., ‘Getting to Yes: Negotiating and agreement without giving in’, Century Business, 1991.

[2]Lieberfield, D., ‘Nelson Mandela: Partisan and Peacemaker’, Negotiation Journal, July 2003, 229-250.